Trophy Beast →

Flabbergasted! I watched from afar in startled amazement as my inamorata Iris was suddenly snatched into a close and tight embrace by my pal Mark and began to dance a jig. We were not in a dance hall or even within 100 miles of one. We were in the high veldt, surrounded by mopane thickets and acacia trees on the white plains of Zimbabwe, East Africa.

I had convinced Iris to come on a genuine outdoor shooting safari. This adventure would not be a champagne safari: butlers serving fine cuisine on delicate china and delicious wines in crystal glasses while overlooking a man-made water hole and tent-top Land Rovers driving to set locations to view posing near-pet lions and other wild game like the Disney Jungle Cruise.

We had flown into Johannesburg and then to Victoria Falls, where the baboons roamed the garden. The next day our hunting team came for us at the famous Victoria Falls Hotel, where water spray from the falls reached high in the air making a cloud.

Our Safari

From here, we drove about 75 miles, mostly on dirt roads, to our first lodge—a yellow hut with two beds, a small shower and a door to keep things out.

Our safari was right out of Hemingway and Robert Ruark—wild, wooly, strenuous, stressful and dangerous. On a typical day, the brilliant overhead sun blazed in a cloudless sky, even in the low humidity of July winter. We walked silently, the elephant grass swishing against our tan trousers. An annoying weed, name unremembered, never stopped trying to get into our socks and shoes. Iris put duct tape on the mesh part of her safari boots to keep this out!

We ate dust. We perspired. We kicked and stumbled over many large rocks strewn on our path, remnants of volcanic action long ago. Occasional bugs and flies added to the torment. Safaris are not inexpensive, so this was costly suffering.

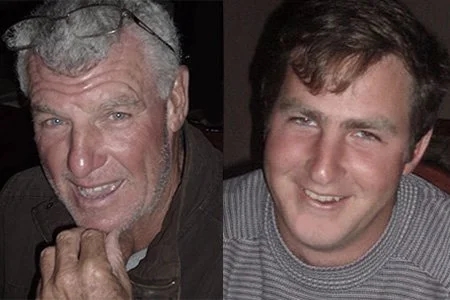

Mark (L) was the senior of our two professional hunters (PHs), along with Tyron. In the era of Hemingway, they would have been called “white hunters.” Mark had an intriguing past and encyclopedic knowledge of the flora and fauna of East Africa. Ruka and another local native guide completed our team.

Our half-million-acre hunting concession in the Matesi region had no human inhabitants, no rain six months each year and abundant wildlife. All the Big Five (lion, elephant, rhinoceros, leopard, buffalo) were present. We saw them all, although the rhinoceros had been reintroduced with little success because of night poachers. The veldt abounded with impala, which continually amazed us with their gravity-free bounding and running. Zebras, giraffes, ostriches, lions, leopards, cheetas, wart hogs and all manner of antelopes and myriad bird life (particularly eagles, hawks and vultures) were ubiquitous. With its strict oversight of wild game, Zimbabwe boasted of a greater variety of animals than non-hunting states like Kenya and Uganda, once centers of managed safari hunting.

Hunting dangerous game on the Zimbabwean plains demands more than a touch of courage and a massive dose of madness. Each morning we arose in the dark at 0530. The temperature was a cold 40 degrees! By noon, cloudless skies allowed the thermometer to pass 75 degrees. After a nice breakfast, we loaded into the hunting vehicle, a specially outfitted Toyota.

Tyron drove, and Iris and I sat up front with him. Constantly on the search for game, the black hunters rode in the back, positioned on a special perch with hold-on rails. In addition to a love of hunting, these talented men had exceptional vision. They seemed to see better with their eyes than we did with binoculars!

On this three-week safari, our goal was to take a Cape buffalo, Syncerus caffer caffer. The sub-Saharan African bovine, referred to as mbogo by the natives, grows to 2,000 pounds and is considered the most dangerous of the Big Five. Experienced hunters often refer to the huge beasts as “Black Death.” Intelligent, cunning, scheming, savage and vindictive, buffaloes must be treated with extreme caution. Hunting mbogo is a long, slow process that requires patience, persistence, determination, skill and maybe some luck.

Two hunts before us, a wounded Cape buffalo charged the hunting party and seriously gored a woman hunter, who had to be flown to the nearest hospital. We heard of this trauma only after our hunt was over, but we knew the risks. Iris and I had purchased one license for a Cape buffalo and a variety of licenses for smaller game. Because I had booked two registered Cape buffaloes during my several safaris on the continent, Iris would take the shot at a trophy beast this time.

On our first day, we had the good fortune to come upon a large herd of about 100 buffaloes. Our PH said that there were two trophy bulls in the herd. For tyro nimrods, it is difficult to discern the sex of a buffalo from afar. To the hunters, the sex appeared obvious. Accompanying us was a government wildlife agent, a knowledgeable young girl equipped with an AK47. She ensured that we did not shoot the wrong animals and that we had licenses for all we took. Misidentification would cause serious problems for us with her and the government. Like most clients, we would take the word of the professionals.

We dismounted the vehicle and struck out on foot. We spent hours looking through binoculars and eons waiting to see what the beasts were going to do. We continually maneuvered to stay downwind, constantly searching for either of the two eligible trophy bulls.

One day, after what had become the usual long, dusty, arduous trek, our PH motioned us to stop. The herd was some distance away, moving slowly and notably inactive. Like a major league outfielder, Ruka, our native guide, threw an occasional rock to try to get some action. The white hunters were keeping their binoculars focused. Iris and I sat down in the five-foot elephant grass to rest. We heard some rustling reeds to our front but saw nothing. Tyron turned to us and mouthed, "Wart hogs." (No talking on safari!). Suddenly, about 10 feet from us, the reeds parted.

There stood a huge female white tusk wart hog with a half dozen little piglets in tow. Iris was in safari duds with a flop hat and huge, round, black sunglasses. The hog stared at Iris, seeming to marvel at her and wonder what sort of critter she was with the extra-large "black eyes." The mother pig shook her head in amazement and pranced off with her tail straight in the air, as only a wart hog can do, leading her litter away. We all smiled and silently laughed at this strange face-to-face alien encounter. Iris did not move a muscle and may have held her breath.

After another long day of hunting, in the gloaming we were headed back to the lodge when there was a tap on the roof. A tap from the black hunters on lookout meant there was something about! In the lengthening shadows, we saw a pride of lions led by a large, haughty lioness, followed by a half dozen younger lions crossing just 20 feet in front of the Jeep. Total immersion in the veldt!

Another late afternoon riding back to the lodge, we came upon a weeks-old cheetah kitten, somehow abandoned by the side of the road. We all dismounted and held the precious, beautiful, furry little cat. It was helpless without its mother. With the wildlife agent glaring, we had no options. We had to leave the little thing where we found it—to face certain death within hours. Ah, nature!

Lining up a shot at one of the two eligible buffaloes was extremely difficult. Most of the time we were about 200 yards from the herd. Once, the wind changed and some young buffaloes on the fringe decided we were a threat and sounded the alarm. The herd was alerted by our scent and stampeded for several miles. Their cloud of dust made it easy to follow their progress, but it was too far away for Iris and me to walk after them.

Now the buffaloes were in a huge circle nearby, more than 100 dark beasts nearly shoulder to shoulder, grunting, bawling, milling about looking for predators (of which we were only one), their hooves raising clouds of dry, dirty dust above the plain. From our location, they could see us but not smell us, so they were apprehensive but not yet alarmed. We knew that in midafternoon the herd would not be moving fast, if at all. Visual contact was imminent. We now crouched down to avoid their view.

The Shot

All of a sudden, Mark, on the point, raised his hand in a sign to halt. He signaled that we were about 40 yards from the herd that we had tracked for four days. On many occasions, we had gotten this close but failed to single out the big old male we were after. This day we were close—so close that if they stampeded our way, we would have been dead in seconds.

Mark lowered his binoculars and turned to Iris, "We need to get closer. Our big bull is almost in range." Iris rolled her eyes and held her breath, heart pounding. The herd broke, whirled and thundered away, but no shot was possible.

By late afternoon of the fifth day, everyone was exhausted and more than a bit discouraged. The eligible buffaloes refused to cooperate and offer a satisfactory shot opportunity.

Ideally, a Cape buffalo is shot from its side where the heart is easy to locate and offers a relatively large target. Different angles reduce the target area. The most difficult angle is from the front, where the vital area presents a spot no larger than the saucer of a small teacup. They told Iris that this was the hardest shot to make.

Once a Cape buffalo charges, it can be stopped by nothing less than a fatal bullet. A wounded buffalo is incredibly dangerous and will double back, wait on its trail and then ambush whoever is tracking him. It is said that even a buffalo shot through the heart can continue to function and rage for at least a minute and a half.

That afternoon, Iris was in front of me about 10 yards with the two white hunters, concealed behind a huge mopane bush. The herd was near but not in view from where I stood. Again, Ruka flung a baseball-sized rock in their midst to make them get up.

Suddenly, I saw Mark open the tripod of shooting sticks and place it in front of Iris. I knew an opportunity must be near! I said a fervent prayer. Buffaloes do not hold a position very long, and hunters must make split-second decisions.

Mark was carrying a heavy Winchester Model 70 calibre 375 H&H Magnum. He hastily set up the stick tripod for exactly Iris’ height, set in the firearm and whispered, "Be sure." Iris knew she might delay but that the Cape buffalo would not! Immediately, the cross-hairs were centered, and Iris squeezed the trigger. Almost immediately, a shot rang out!

Then Mark grabbed Iris and hugged her while she was trying to dance a little jig. I knew she must have shot perfectly! Missed Cape buffaloes run away. Wounded buffaloes either charge or run away and must be followed at once. This Cape buffalo had presented only a front shot. Iris had taken pinpoint aim, hitting the trophy in the heart and on through to the spine, dropping it instantly dead. The animal was 1,700 pounds with a hide as black as the basement in Hell.

Our white hunter had seen this happen only twice in 28 years. Iris asked, “Did I shoot it where you told me?” Mark responded, “What difference does it make? He is dead!”

Post-Hunt

Iris donated her buffalo meat to local cooks to share. Remembering their beaming faces, she will always be able to say, “I once went on a safari and downed a Cape buffalo with a single shot. I am pleased to say that I fed many hungry people in Zimbabwe that day.”

Epilogue

As Iris and I reflect on this great adventure, we shall never forget walking toward the dead Cape buffalo with our friend and professional hunter, looking down on the dusty old patriarch. Grinning fiercely, Mark hugged us both. With a hint of a tear in his eye, he said, "Nothing like it, is there?”

Our buffalo hunt took the first five days of our safari. Over the course of our three-week hunt, we probably covered more than 200 bone-jarring miles in the vehicle, all off road. The truck ran flawlessly, but we were often interrupted by flat tires from sharp rocks and sticks. In addition, we walked, shuffled and stumbled at least 30 miles over the terrain—rock-strewn, rough and hilly.

We will never forget that Iris with one bullet shot dead a 1,700-pound trophy Cape buffalo, one of the most dangerous of the Big Five trophy game animals in Africa.

Her successful shot was a special surprise, and the dance music was in our hearts and minds. The memories from a great safari are its greatest reward and will succor us when we grow old, reminiscing around a virtual open fire, sundowner in hand. The celebration dance goes on and on for a lifetime!

Iris and I like to name things, so it was appropriate to give this trophy-book behemoth that brought so much frustration, adventure and satisfaction to our lives an appropriate moniker. “Rodney” fit the bill! His mounted head adorns the wall of a room we now call "Rodney's Room" at Oaklea. Rodney is a present reminder of Iris’ phenomenal shot and our magical safari in Zimbabwe.

Brief story video.

Photos of map, warthogs, lions, cheetahs and buffalo herd are licensed from Adobe Stock.Bonus Audio: Listen to Hemingway’s Cape Buffalo hunt stoty, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Available free and immediately on YouTube: https://youtu.be/ct-vhTrKKGg?si=B9qwAlBEN1fMmjtO