Coming of Age

I found release from many a secret struggle while hunting animal adversaries both subtle and strong. This evenly matched battle between human intelligence and the wisdom of wild beasts seemed strangely clean compared to the snares set by men for men.

Memoirs of Hadrian, Yourcenar

When Charlies dropped to his knees, I knew that finally, regrettably, after all the long tedious days and wearying, terror-ridden nights, the end was at hand. My mind flashed back to the dangers we’d survived together; the cold meals we’d shared, and the seemingly infinite bone-jarring miles we’d covered in our Land Rover crossing the high veldt of Zimbabwe, Africa.

Charlies Aardvark was his name. Actually, Charlies’ surname was Sibana, which in the Ndebele language means aardvark, or ant bear. This is a rather common and complimentary name because these animals are accorded considerable respect for their intelligence. For the given name of “Charlies,” there is another explanation. Taking an English name, which took root long ago, began as a way of identifying with the ruling class. Now it is a custom, with names like “Bicycle,” “Radio,” “Belt,” “Goodwill,” “Stomach,” and so on.

Charlies, of course, was obsidian black. Dark as soot. He stood no more than five and a half feet tall, was quick to smile and was blessed with eyesight said to be 20/5, or whatever equates to the ability to read at 20 feet what normal eyes read at 5 feet. Charlies was also the wealthiest black African I’d ever met, measured by black African standards. At twenty-five he already had three shiny, fat wives, all pregnant, and thirteen children. That is mega-wealth in tribal Africa, where children are looked upon as assets. Girls bring rich dowries for marriage, and boys provide financial support during old age. Ergo, the more children one has, the more material possessions, or wealth and peer respect one attains. But the same premise applies here as in our capitalistic society. It takes money to make money. This translates simply. It takes wives to have children, and it takes money to buy wives. Charlies earned his first money from his intuitive, natural talent and skill for hunting that was greatly enhanced by his phenomenal eyesight.

Charlies and I became friends on safari in June 1985. Not “safari” in the modern interpretation of the word, implying zebra-striped minibuses jammed with blossom-shirted, package-deal tourists, clicking modern equivalents of Kodak Brownies at lazing prides of lions—lions accustomed to both tourists and the easy life of a game preserve.

No, that kind of African expedition was not where we would meet. Ours was the type of safari made popular by Robert Ruark and Ernest Hemingway. The safari of stalking trophy animals in the wild with the intent of killing them before they did you the honor. Ours was the safari filled with genuine danger and real fear that can make one sweat in freezing temperatures. Ours was the adventure that could, and frequently did, become the last excitement of a lifetime.

Only months before, in the same Matetsi area of Zimbabwe where we would be hunting, two clients had come to grief. A young lady on her honeymoon decided to photograph a cow elephant and her calf. Her professional hunter, today without a license, failed to heed the number-one rule when on safari: Always carry a proper firearm. Running from the angry mother elephant, the girl fell over a root and instantly became the object of the pachyderm’s rage. The poor girl was paralyzed for life from the neck down. Although elephants at the circus appear to be docile, on safari one must remember they are both intelligent and unpredictable and can be extremely dangerous.

Another hunter wounded a leopard late one afternoon not far from our lodge. Unable to track the wounded animal, the hunters returned to their vehicle, only to find the injured cat waiting there for them. The client was attacked and only escaped with his life because of the bravery of the professional hunter. It took over 200 stitches to sew him back together, and he never will regain full use of his damaged arm.

Safari stories can be told ad infinitum by those who have been African explorers. What of my friend and fellow hunter, Charlies, kneeling in front of me? Charlies kneeling in front of me? Charlies hadn’t dropped because of a lion bite or because he’d been trampled by an elephant or gored by a cape buffalo, though we’d shared dicey experiences with these beasts He was on his knees in front of us because his customs taught him that this was the greatest compliment he could pay someone. He had dropped out of respect for my wife and me. I was honored to be so beknighted by such a fine hunter and person as Mr. Aardvark himself. Although most of my major exploits had been in his company, my grandest accomplishments occurred in the bush at night when Charlies was sleeping in his hut with his youngest wife. I took a trophy lion, and Charlies had played a large part in arranging it.

My 80-year-old father was also on this trip. Since I was a youth, filled with Edgar Rice Burrough’s tales of Africa, it had been my ambition to stalk and take the grand trophy animals. Foremost, I wanted the King of Beasts, the mighty feline we call lion, pantera leo. And mighty he is, in both legend and fact.

With awesome 40-foot bounds, a lion can cover nearly 75 yards in three seconds. He can hold an entire watermelon in his mouth without breaking the rind and jump an eight-foot fence while carrying a prey nearly equal to his own body weight. A lion’s eyesight defies quantification and is equally good day or night. Hearing, sense of smell, camouflage and cunning added to its incredible strength make the lion one of nature’s most efficient creatures. A lion has only one natural enemy—Man, who is superior to the lion in intelligence.

So, why would a 50-year-old man who enjoys a certain measure of financial independence, has a lovely wife and family, a comfortable place to live and a nice collection of art and vintage automobiles, want to risk his very life hunting such wild game? The answer, I suppose, is that I enjoy being tested. Tested mentally and physically to measure my courage in absolute, concrete terms, independent of the judgment of others. The thrill of a great challenge affects me the same way catnip affects a cat. Dangerous situations bring an added intensity to life, and sharing such adventures with others creates a camaraderie that can be found nowhere else. When you risk everything, you have the opportunity to look within yourself. As at no other time, you see your true mettle.

Zimbabwe has an efficient and well-run hunting industry, governed by dedicated professionals. It is a major source of hard currency for this relatively small and once-prosperous nation. Hunting concessions are generally let to the highest bidder for three-year periods. All hunting is carefully monitored and supervised, and detailed daily records are a must. Most game taken is inspected by the government. In effect, the clients paying foreign dollars are no more than a temporary adjunct to the game department. Under the supervision of professional hunters, both black and white, the very oldest males are taken as trophies. Invariably, these animals are nearing the end of their lives and not infrequently have already been driven from the herd or pride because of their age. The work of this Zimbabwean bureaucracy shows an awareness of the essential role of hunting safaris in scientific wildlife management.

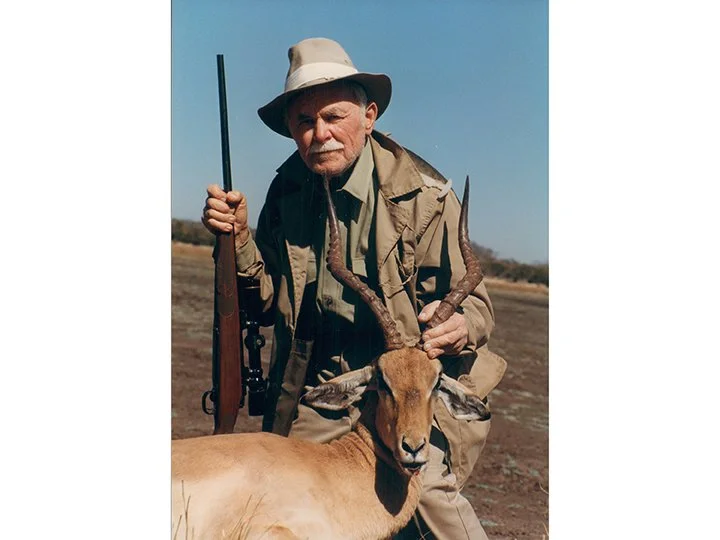

During our hunt, we had nearly exclusive access to over 500 square miles of wild and uninhabited land. The country must certainly have been the same eons ago. I can imagine an ancient evening with lions roaring and moon shadows dappling myriad animal forms. The scene was probably followed by a brisk morning indistinguishable from the early part of this day as graceful impalas bounded a joyful ballet.

The lodge for Victoria Falls Hunters, our concessionaries, had been the homestead of an unsuccessful cattle rancher. Lions, ticks and a lack of water, the traditional problems that can make it difficult for cattle to survive in Africa, combined to bankrupt him. He and his neighbors found partial salvation when the government purchased and combined their failed ranches into national parks and hunting concessions.

The lodge was nestled comfortably atop a precipitous green hill overlooking a modern, man-made water hole about 300 feet below. Stucco walls rose above a handsome, massive fieldstone foundation. The roof, a heavy grass thatch, had been aged by over 25 years of African rain, dust and relentless sun into an impenetrable cover.

This comfortable dwelling rested serenely under a stand of huge mopane trees, artistically soaring toward the clear African sky. They dwarfed all others in the immediate area due to decades of human attention in the form of water. A huge baobab tree, centuries-old, 20 feet in diameter and shaped like some growth from a science fiction movie, cast weird shadows over the very important skinning shed. Assorted brilliant flowers and shrubs produced a panoply of color in the cool, church-like shadows. The grass on the lawn, as green and perfect as a golf course, was where peacocks strutted by day. By night, they perched on the furthest limbs of the mopane trees for protection from leopards. The peacocks screeched at unlikely times.

The lodge was surrounded by an eight-foot barbed wire fence, ostensibly for the protection of the camp contingent. But because lions can jump over eight feet and hyenas can dig under, the fence was more symbolic than functional. On the way to breakfast our third day at the lodge, my wife and I had spied leopard tracks in the dew!

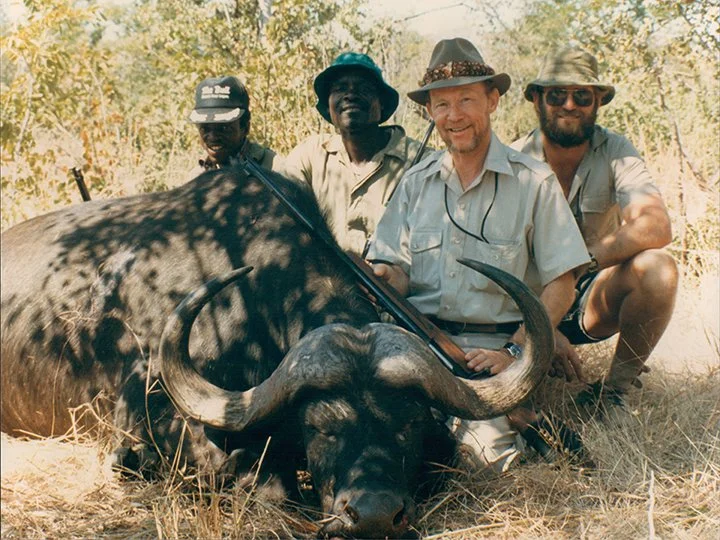

The safari staff was extensive. By order or rank, there was the black concession co-owner, whom we only saw once. The most important player was our white hunter Cornelius Van Wyk, one of about 75 licensed professional hunters in Zimbabwe. He is fourth-generation native, the decent of Boer (Dutch) settlers who opened South Africa in the last part of the 19th Century. His family owned a sizable ranch in the central part of the nation, but Con’s love is the hunt, not cattle raising. During the decade of civil war as Rhodesia was being turned into Zimbabwe, he was in the military. He lived on patrol with a rifle in his hand. Our very own Charlies was his number-one scout. Con’s tales of combat are hair-raising as are his stories of safari. His only life and love, aside from a charming wife and three daughters, is the hunt. His knowledge of the fauna and flora is encyclopedic, his storytelling is hypnotic and his judgment of trophies in the field is incredible. Con is a white hunter in the heroic mold described by Ruark and Hemingway.

In addition to Con, we were staffed with Charlies (the white hunter’s black tracker), Alfred (the black tracker belonging to the concession), various skinners, a major domo, a chef, his assistant cooks, a laundress and a multitude of lower servants. All told, including families, well over 100 people lived in the camp. Most of the blacks lived with their families in a compound of beehive huts, where cooking was done in tin pots over open fires. Each man was restricted to one wife in camp, so it was not unusual for them to rotate wives, allowing each the opportunity to enjoy a bit of this luxurious life style.

An immaculate vegetable garden insured a full and balanced diet, though be reminded that a safari-African is paradise for meat-eaters. I helped see to it that there was no hunger in camp. A 10,000-pound elephant I shot was stripped to the bone, leaving slender pickings for the ants. The meat was marinated overnight in finger-sized strips, then air dried to last indefinitely. What my ancestors in Kentucky called “jerky” is called “biltong” in Africa and is just as practical and tasty.

There are three basic ways to hunt lions in Africa. Perhaps the most challenging is to track or spoor them, to find and follow trails right to the lion. The overall difficulty and increased danger of this approach with no opportunity to select the trophy argue against it. Generally, the cats will be found in some thicket bedded down for a midday nap, and even the most careful pursuit usually ends with a warning grunt and the lions rushing off. At best, this method offers the hunter a quick shot at a departing lion of indeterminant size and mane.

Another method is to find an area where lion have frequently been seen, then search for natural kills, which can be pinpointed by vultures circling or perching in nearby trees. Listening to roaring before dawn and proceeding at first light to that area is another way to find lions. This method works best in open land affording good visibility.

The method most practiced, however, is baiting. The advantages here are that the hunter can view the potential trophy and thereby better select an exceptional specimen. A carefully aimed shot is usually available. The disadvantages are that it is cold and uncomfortable, takes much patience and is dangerous.

Lions, like most people, do no more work than is necessary. Consequently, a lion prefers to feed on a dead animal rather than stalking and killing a live one. Thus, baiting is the logical way to hunt for a trophy lion. Lions are plentiful, but how do you find the old, large-maned male you want for a trophy? This can be done only through persistence following every spoor, hanging lots of bait and spending hour upon hour silently watching. In addition, you need fantastic luck.

Each day our search for lions began well before light. With the first hint of morning nautical twilight, we set forth in a Land Rover following many crisscrossing game trails. Luckily, these “elephant wide” trails, created over centuries by the huge lumbering animals, formed the same width track as our vehicle.

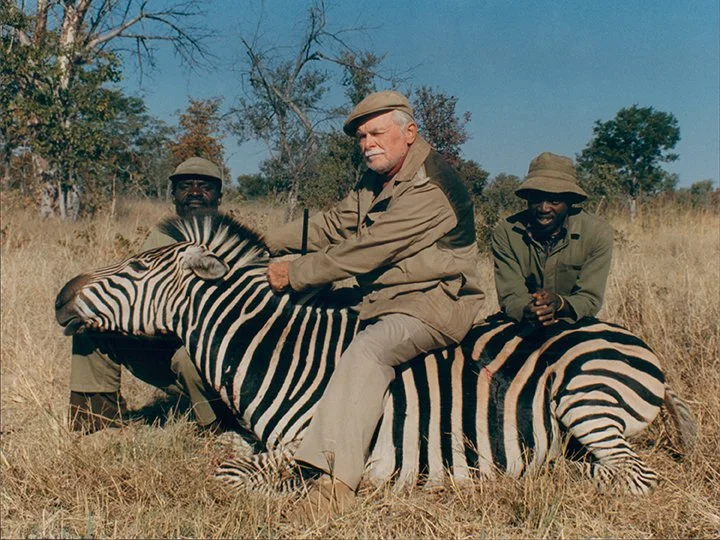

At first light, all eyes in the Rover were alert for spoor in the dusty terrain of wintertime Africa. (For professionals, this is less difficult than it would appear.) Any tracks were analyzed for freshness. If tracks were recently made by what appeared to be a large, older male, we were in luck. On a limb of a suitable mopane or a gray bark marula tree nearby, the front or hindquarter of a dead zebra was hoisted and secured by wire to hang about eight feet above ground. In this way, a lion could eat some of the bait but would be unable to reach the very top. If the lion finds no other food, it will continue to toy with the morsel that is just out of reach.

At one time, we had six hunks of putrefying meat swinging in the African breeze to drum up a trophy. With baits out, our day began by cruising these to see if there had been any takers. In the early light, we stopped the Land Rover downwind about 1,000 meters from each bait and proceeded on foot to check it. This walk was made on alert with our rifles at the ready as there was a chance we might surprise a lion or lions eating breakfast.

One morning the excitement intensified and the hair on the back of my neck stood on end when we found a hunk of zebra partially eaten. The size of the prints indicated a trophy lion was in the area, so we constructed a blind in a clump of trees about 50 feet away from the reeking meat.

The black hunters brought out their treasured knobkerries, native axes that had been individually blessed by the witch doctor. They cleared underbrush in a line of sight around the clump of woods and constructed a shelter there with wire, vines and reeds just large enough for us, the hunters. They cut and placed a few thorn bushes around the blind to discourage investigation by a lion. The black hunters stood back and admired their handiwork, smiling like Tenderfoot Scouts on their first camping trip. Because the reeds were chopped with axes blessed by the witch doctor, the structure itself was likewise blessed.

To me, the blind looked like an early model of the straw house one of the “Three Little Pigs” built, and I knew what happened to it! Con was satisfied with the job, so we spent a short day searching for other trophies on my license and inspecting the other untouched baits.

Despite our good intentions, we got back to base camp later than planned. We wolfed down sandwiches, loaded gear into the Rover and changed into warmer clothes. The sky was turning the first shade of red, signaling the start of a fleeting African sunset as we set out across the bumpy elephant trails. We were headed for the straw blind that would serve as our evening’s lodging. Con was driving as fast as safely possible, because we didn’t want to enter the blind in the dark. Lions sometimes feed prior to sunset, so we wanted to get into position quickly.

A half mile from the baited tree and blind, he stopped the vehicle in a small cloud of dust. Con, my wife Lee and I loaded water jugs, sleeping bags and aluminum chairs in our arms and hurried toward the straw enclosure. Con and I had our rifles at the ready and our eyes wide. Surprising a feeding lion at twilight is an extremely unsafe practice.

Creeping up to the site, we could see the half-eaten bait silhouetted against the slate-grey sky. There was no sign of the cat. Trembling with excitement, we first stuffed our gear into the blind, then on hands and knees crawled into the straw cocoon that was to be our home for the next 12 hours. It was late June, wintertime in Africa. Eleven hours of darkness each evening made this nearly the shortest day of the year in the Southern hemisphere.

Sounds take on a new meaning in the wild. Normal cotton khaki clothing worn in the bush is incredibly noisy in a blind. Any movement that causes straw to scrape cloth sounds like a signal shot. To guard against unwanted and potentially dangerous sounds, we wore our softest clothing on the outside (sweatpants and cashmere sweaters).

During the days that were uniformly sunny, clear and dry, the temperature had hovered just above 70 degrees—magnificent to say the least. At night, it was another story. The mercury made a hasty retreat toward freezing as the sun set. It is difficult to sit absolutely still under the best of circumstances. To remain motionless for a prolonged period of time in the intense cold when you are shivering from fear anyway is not easy. Nature tends to call as well, but that call is imprudent to answer.

After a period of discomfort, my body allowed my mind to withdraw and detach. My thoughts drifted, but not far; my eyes closed, but my ears remained alert, sorting out the myriad night sounds of the African wild. For a time, it was so quiet that I swore I heard nothing but the sound of my own blood flowing in my veins.

The pads on lions’ feet are well adapted for noiseless movement. It was probable we would only realize they were on the bait once feeding started!

The reverie was suddenly shattered by a gruff snort, not a lion sound. I don’t remember who told me that “things you don’t know can’t hurt you,” but I do remember having no faith in the saying. I recall, in vivid slow-motion, frame-by-frame detail looking out the peephole in the blind. Above in the cloudless sky, the silver moon cast eerie shadows about. Staring through my binoculars, my eyeballs searched for the source of this primitive grunt. It had sounded like a huge wart hog. Slowly I turned the focus knob in an effort to define and separate the shadows.

A grey, hulking blob came into focus and took shape 15 meters away—a black rhinoceros. The most irrational, stupid animal in the veldt, this creature has a reputation for attacking and leveling reed blinds with gusto. There was nowhere to hide, and the protection that my .375 H&H magnum rifle afforded was questionable. As endangered species, rhinos have been moved to the Matetsi to give them a chance to recover and procreate. Even a self-defensive shot at one can result in a jail sentence, so we had a Hobson’s choice: no choice at all.

An eternity passed in minutes as the snorting and snuffing continued. The beady eyes of this survivor of prehistoric times seemed to be staring directly at our pitiful hiding place. Then with a shake of its head, this thick-skinned, mental reject ambled off in search of other territories to conquer. Silently, in the half-moon light, we the watchers, the near-victims, celebrated the welcome departure of this nemesis with the language of glances. I hadn’t taken a breath for hours as the sound of my heartbeat rang in my ears. The nervous sweat on my forehead turned cold. The moon rose above the mopane trees as I tried to rest, my cap pulled over my face. My eyes remained on full alert.

Because they are predominantly nocturnal animals, lions probably feel safer under the cover of darkness. Seldom will they show any interest in a blind, and they seem to ignore the obvious scent of humans, focusing instead on the bait.

A noise that came straight from hell sent all my systems to their battle stations. A lion was tearing off 20-pound hunks of decaying zebra meat just 50 feet away. Looking through my glasses, the sinewy form of the animal was clearly visible in the moonlight. I could never recall trembling so from a combination of cold and fear—10% cold, 90% fear.

Con touched my shoulder and shook his head. No, this was not a trophy lion. I glanced at Lee seated between us in the moonlight like a rabbit transfixed, carved from alabaster. I detected neither movement nor breathing. Was she braver than I or just more scared?

The lion fed greedily for a long time, then moved silently off into the shadows. There was no more action that night, and none was needed. Just after daybreak we loaded our gear back into the Rover, looking somewhat like new scouts after their first night camping out. Everyone was clearly disappointed.

Days passed in succession one after the other. Lion spoors were in evidence everywhere as we went about the business of hanging baits from gnarled mopane and elegant acacia trees. We even dragged zebra entrails for miles to give the lions clues as to where the juicy haunches had been hung. They ignored all our offerings, having apparently killed all they could eat. Hyenas and vultures occasionally stole the bait, to the consternation of everyone. The wild, hot beauty of the Matetsi was forgotten. My mind became numb from concentrating on just one four letter word—Lion!

I’d booked the hunting concession for 23 days, and each day we’d focused on lion, to me the most important trophy. I’d used up 10 days of the hunt and had taken some fine trophies, but no lion. I was depressed, dejected and discouraged. To counter these feelings, I kept thinking of that timeworn saying that “it’s always darkest before the dawn.”

Very early one morning we were traversing and hanging baits, when the black hunters standing behind us in the bed of the Land Rover tapped on the roof of the cab. It was the signal for us to stop. The morning cold had yet to lift, and wisps of fog still clung to the draws and hollows. I yawned and stretched while the three hunters bent over staring at the ground. Charlies looked strangely out of place in his khaki cotton jump suit and a tattered formal men’s coat he wore to ward off the cold. Suddenly everyone began grinning like a bunch of mules that had just eaten briars. Con quickly enlightened me. “Two extremely large male lions just passed, minutes ago.”

Happily we set off afoot in single file with me bringing up the rear. For perhaps a half-mile, the spoor that were easily visible in the dust followed the elephant trails. The paw prints were huge, easily eight inches across. I carefully slid back the bolt on my rifle to make sure a round was in the chamber. A gleam of brass assured me there was.

In the clearing on a small rise, I saw Charlies, who was in the lead, suddenly freeze. My heart rate made a quantum leap as adrenalin power-pumped through my system. We sidled across the clearing together and came on the signs of a blood struggle strewn on a crushed bed of wildflowers. The entire intestinal contents of a zebra was steaming in the early morning cold. The lions we’d been stalking had apparently been doing some stalking of their own. Unlike our hunt, their hunt had been successful.

The lions had apparently surprised the zebra together. Con said that one of the cats had probably hooked a huge claw on one side of the prey’s neck and snapped it with the other paw.

Con and I were in the lead, side by side, about 10 yards apart, followed closely by the unarmed black hunters. I held my rifle across my chest with the barrel forward, much the way a quail hunter about to flush a covey might. I flicked the safety off as we started down into a draw covered with thick underbrush. The trail where the dead zebra had been dragged was obvious even to me.

A roar from Satan’s den brought us up short. No animal can be louder than the lion. About 40 yards away across a small draw, a huge, menacing, swarthy lion was telling us in no uncertain terms we were trespassing. As I aligned the open sights on the lion’s shoulder, Con whispered emphatically, “Don’t shoot!”

The lion crouched, his tail twitching and with a frightful roar bounded our way. Charlies made a rapid exit into the bush behind yelling out one of the few words in his English vocabulary, “Shooting! Shooting!”

“Don’t shoot!” Con yelled, countermanding Charlies’ plea. I didn’t, but I was ready to at the very moment the lion came to a halt. Just as quickly, he turned and triumphantly sauntered back into the bush. This is called a “mock charge” and is characteristic lion behavior. A “mock charge” is frequently the ploy a lion uses to establish his territory or property. At this point, any intelligent creature is best advised to beat a hasty retreat and be thankful the charge stopped short.

A tremble rippled down my spine. The charge had not been straight, but full of jerky feints, like a halfback in football. At the same time though, the lion had covered ground like a top-fuel dragster. My instructions had been, if confronted with such a situation do not fire your one shot at the lion until he makes his last pounce toward you. This pounce would be 500 pounds of cat traveling at 30 miles per hour, mouth open and massive claws outstretched like knives.

“Be sure to shoot him in the mouth,” I’d been told.

“But won’t he hit me anyhow?” I’d asked.

“Certainly,” I was assured, “but if you shoot accurately, at least he will be dead when he hits you.”

To me, it did not sound like a very desirable position to be in.

It is an accepted fact that black trackers generally run when an animal charges. White hunters, however, consider running to be cowardly and a demonstration of poor judgment. Black trackers think just the opposite. With a nod of his head, Con motioned me to continue with him into the “lion’s den.” My adrenalin was pumping to the max.

The lions were gone, but the warm zebra was there minus its liver, the first morsel they’d eaten. Where both cheeks of the rump had been, a thousand ants now crawled. The lions would be back, Con assured me.

“Why’d you tell me not to shoot?” I asked Con. “I had a good shot.”

“That was a huge lion,” he said, “about as big as I’ve ever seen, but he had no mane. His partner had a good mane and perhaps is even a bit bigger. A trophy must have a good mane.”

Our black hunters had reappeared, so with a rifle in port arms position, Con jogged off for the Rover while Alfred and Charlies began clearing out the underbrush with their native axes. Our plan was to steal this fresh kill from the two large hungry and undoubtedly angry older male lions and hang it as bait in a tree. I fully expected we would be attacked at any instant during this exercise and considered the idea of my skull popping like a grape under the pressure of those massive jaws. However, in this survival of the fittest, I intended to be the “fittest.”

A few hundred yards away was a setting right out of a hunting textbook. With the limb of a nice-sized mopane tree as the hanger, we would use the vehicle to pull the 800 pounds of zebra up into position. Charlies slit the skin between the bone and tendon of the zebra’s hind legs, ran the wire through the slits several times and half hitched it. A rope was tied to the wire, which in turn, was thrown over the limb and attached to the trailer hitch on the Rover. The vehicle was then used to pull the meat up into the tree. When this was done, Charlies shinnied up the trunk and tied the leg wires around the massive tree limb.

While the hunters finished hanging the bait and began constructing a blind, I recalled a native proverb. It says a brave man is always frightened three times by a lion: first when he sees its tracks, second when he hears it roar and third when he first confronts it. I noted that the proverb put no limit on the number of times a man could be frightened, it just set a minimum number. Indeed, I reflected.

My spirits had improved. After 10 days of intense lion hunting, we had spotted or been spotted by quarry that seemed suitable to take as a trophy. Now we had them on the ultimate bait, their own kill.

The lions we were hunting were old enough to be outcasts as they no longer had the social graces to be acceptable mates and fathers. For a male lion, such status is tantamount to relegation to a nursing home. As they grow older, male lions come to depend primarily on their reputations rather than their actual performances. If a herd of appealing food is spotted, the females do most of the hunting and killing. Sometimes a vain old male will saunter upwind to scare the prey animals toward an ambush set by the females. The females kill the prey and bring it to the lair where the male eats his fill, occasionally allowing the cubs an indulgent bite. Then the females feed.

The lions we were preparing to confront did not and would never again have the attention of the females. They were on their own in the twilight of their years. Without obliging females to provide most of their food, their physical condition would begin to deteriorate, which in turn would make it more difficult for them to hunt adequately on their own. Although they were in the downward, terminal spiral, they were still a long way from being a meal for vultures. They were extremely dangerous, wise old lions.

Long before sundown, Con and I were in the “hide,” as they are sometimes called. I had positioned two “Y” sticks to hold my rifle in the general direction of the bait. By levering the stock up to my shoulder, I had a near-perfect, bench rest shot of 17 paces. I would have felt more comfortable with my larger caliber .375 H&H, but it was scopeless and odds were good I’d be making a low light shot at dusk or just before sunrise. My 30.06 Winchester Model 70, with its scope adjusted to maximum magnification, packed a 180-grain round.

In the blind, we made ourselves as comfortable as possible and awaited both the darkness and our destiny. The sky turned platinum, then became streaked with rose and mauve, and finally changed to an ever-darkening grey. Although it was nearly full, the moon would not rise until nearly 9 p.m.

Now I could barely distinguish the trees and bushes from their shadows. African night sounds provided the score for our drama. The stage was set, but the principal players were nowhere to be seen or heard. I fidgeted and stretched.

Suddenly Con’s hand was on my arm, squeezing it in a way that told me the show was about to begin. From our right, two large shadows making absolutely no sound moved directly toward the hanging zebra. I tried to line up the crosshairs to see if a shot was possible, but the scope was a kaleidoscope of black and grey. Nothing was discernible except motion. It was too dark to shoot. The lions pawed the zebra a few times, then without fanfare they suddenly merged with the blackness.

Con spoke in a normal voice, startling me. “I was afraid of that. Those cats were spooked because we handled their kill and left human spoor all around.”

“What now?” I asked.

“We’ll wait for the moon to rise, then leave. I’m afraid we must find some other lion for your trophy.”

My spirits nosedived. What had seemed possible, in fact nearly in the bag, was now out of the question. My safari was half over, and my trophy seemed as elusive as ever.

Con rose, stretched, picked up his gear and crawled outside. I followed, my spirits at an all-time low. A dejected pair of hunters made their way through the brambles and dust toward the Land Rover.

We were walking in silence keeping our thoughts to ourselves when a bloodcurdling growl split the air. Although we could see nothing in the dark, no more than a few yards away was a lion or lions. It was a long way back to the blind. Our safeties were off and our eyes and ears were as tuned as they could possibly be. Con had been wrong. The cats had not disappeared. They were out there waiting in the dark, perhaps crouched and preparing to pounce. These lions could not only hear and smell us, they could see us and if they were so inclined, they could easily kill and eat us. We were in a decidedly untenable position.

“Let’s see if we can make it back to the Rover,” Con said in a low voice. I like that, “Let’s see if.” No one ever said a safari wasn’t dangerous or exciting.

As we quickly moved toward the scant security of the open vehicle, the grass seemed to crunch and crackle underfoot like eggshells. Louder than the roar we’d heard moments before was the sound of my heartbeat. Fortunately, we heard no more from the lions. When we reached the vehicle, the cold steel of the door was welcome, and the sanctuary of safari headquarters was even more welcoming. Whoever said that a lion scares you three times was way off.

Winston Churchill said he always preferred chilled champagne at the end of a nice day on safari. Under normal circumstances, I did as well, but this evening called for stouter measures, such as a nice glass of whisky. Besides, this was my 50th birthday, and I was a long way from my roots in Kentucky.

Sleeping in the lodge, my fitful rest was punctuated by frightening dreams. I dreamt I heard a big male lion roar, boasting of his prowess, announcing in no uncertain terms that he was king of beasts. The sound, deep and base, made the short hairs on my neck stand on end. I awoke in a sweat. I was not dreaming! It was half-five (white African slang for five-thirty) in the morning). At just that moment, there was a knock at the door and in came Nick, our major domo with my morning pot of coffee and toast made from freshly baked bread. My wife, Lee, who was to accompany us this morning, so on the platter was her usual breakfast: a bacon, lettuce, tomato sandwich on toast with plenty of mayonnaise and a coke.

Fifteen minutes later our squad of five people was on the trail, huddling against the cold in the first glimmer of nautical twilight. Our first stop was at the blind where we’d seen action the evening before to inspect the hanging zebra.

Nearly a mile from the site, Charlies signaled for us to halt. When we stepped from the Rover, I saw that the trees were filled with vultures, a sure sign that lions were near. If there were no lions in the area, the vultures would have been on the bait, or what remained of it. Vultures venturing injudiciously within paw-swipe range of a lion made no further contributions to the vulture gene pool.

We formed a line with Con and me at the head, then Charlies with the extra rifle, then Lee and, finally bringing up the rear, Alfred. We passed a bleached impala skull, glistening wet in the morning light. The tall dew-covered grass was soaking my boots and clothing.

Here, mere hours before, we’d had our most recent confrontation of sorts with the lions. How would they take to our continued interference? We had to assume they would not be in a particularly good humor.

Surprisingly, the entire zebra carcass was gone from the mopane tree where it had been hung by the heavy wire! When the powerful cats had decided to pull it down the wire offered little resistance. But at least the remains of the carcass was near . . . . as were the dangerous cats who had killed it and taken it back from us interlopers. I knew they would be ecstatic to see us so early in the morning. A power breakfast of sorts.

In a cozy spot beneath a magnificent artistically shaped acacia tree, on a spot of flattened grass, lay the remaining half of the zebra. Lions can eat about a quarter of their own weight at a sitting. Before us was an impressive display of their appetite. They had not awaited our arrival to move on, having departed only seconds before we came on the scene, Charlies said. On an open slope across a draw, a jackal with a white tipped tail nonchalantly trotted away, no doubt unhappy with this turn of events.

So what did we do? We cleared a path and drove the Rover into position, attached a rope to the zebra carcass and stole it for a second time. How to win cats and influence lions. We rehung the bait from the same tree, this time using twice as much wire. As we were finishing, the delicate copper pink blush of the dawn sky was fading, to be followed by the crisp freshness of a new Zimbabwean day. My dreams still held the possibility of fulfillment.

My life has had more than its share of adventure and excitement. Many experiences have been in special or isolated environments; on racetracks, bobsled runs, mountains, caves or coral reefs. But here, in Africa, the entire outdoors is a set for the ultimate adventure. Here nature remains as it was a million years ago before man became so dominant over the environment. In the African bush, it is all “Life and Death” on the big screen.

We all tend to draw circles and set parameters around our lives, then live within those confines. A safari shows in graphic, gripping, intense ways that other interpretations, other circles and parameters are possible when and if you break through your artificial self-imposed limits. On safari, there can be occasions where everything, including your very existence, is at risk. At these times you have the rare opportunity to look inside yourself and conduct a special inspection. More than one morning as I slipped my coffee and pulled on my boots in the dark, I considered that this just might be the last day of my life.

Back at the scene of action I asked Con if he thought the lions would return for the bait.

“I doubt it,” he said. “we have handled it so much, but, I was wrong the last time.”

Later that afternoon, the two of us were back in the blind; my Winchester propped in the “Y” sticks, ready for the same 17-pace shot at a trophy. I was in need of some luck and kept crossing and uncrossing my fingers. The sun set and the softness of eventide brought a peacefulness to the now-familiar landscape. The stillness of evening enhances the sounds of the veldt.

The sound we awaited needed no enhancement and shortly it came. An awesome, belligerent roar not far away. With a smile and several hand signals, Con advised me “our” lions were indeed returning to the bait, apparently having had no success killing new prey.

I felt a rivulet of sweat run down my chest, in spite of the rapidly falling temperature. My moment would soon be at hand.

Another reassuring roar. Closer this time. And another, still closer. Finally, through eerie shadows, the huge cats padded up to the rank meat. My binoculars were glued to my eye sockets watching the maneless cat rip down huge chunks of zebra, each the size of a rolled roast, and wolf these down hide and all. Lions chew their food little, letting their stomachs do most of the digestive work.

My trophy, the old boy with the mane, lay in the shadows, allowing his younger companion the first go at the zebra. No shot was possible where he lay. While Maneless continued to stuff himself, the light began fading at an ever-increasing rate. If they did not change places soon, I’d be unable to get so much as a silhouette shot. “Damnit,” I cursed under my breath. My prize was so close! But I needed a clear shot. The result of a poor shot would not only be an extremely dangerous wounded cat, but it would cost me the same as a good, clean shot—$1750. It would also be my last shot, as I only had one license.

Maneless tore off and swallowed a final volley ball-size hunk of three-day-old, raw zebra meat and flopped on his back in the grass. The shadows near him stirred, and out of the gloom my opportunity appeared. Con touched my shoulder with a combined “go ahead/good luck” squeeze.

My trophy took charge of the food with authority. He ripped and tore at what was left of the carcass, gorging himself on the rancid flesh. What kind of life had this “king” lived? No doubt he had killed and eaten his share of game over the years, and fathered perhaps a hundred cubs. His moment of immortality, of sorts, was at hand and in my control.

Last light was upon us when I moved my eye to the scope. I was awaiting a profile shot. I’d studied the anatomy of a lion and knew where the heart was. The huge cat continued to lunge upward on its hind legs, ripping hunks of meat from the carcass. Finally he dropped on all fours and stood broadside. In the intense gloom I couldn’t see the cross hairs that should have been transposed on the shadowy form. At that moment something inside told me it was now or never. I calculated where the cross hairs should have been if they were visible and squeezed the trigger.

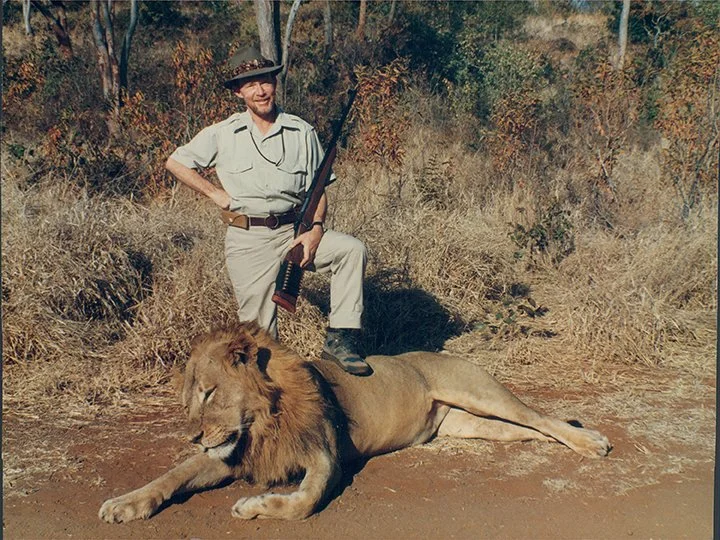

The blinding flash, loud report and smell of cordite was followed by a huge roar. I had struck home. Another feeble roar and my trophy lay down softly dead.

From a mortal, aged, over-the-hill king of beasts, my lion, in little more than an instant, had been transformed into an immortal, ageless trophy to be honored and talked about for decades. Could the King of Beasts expect a more honored after life?

There was silence and pitch black darkness until Con spoke in a whisper. “Congratulations. A splendid shot. Now, we must wait to see what the other beast decides to do.”

I leaned back in the aluminum chair within the blind and felt my heart rate gradually decrease. My forehead felt damp. I rubbed it with the back of my hand then held it up to my eyes. Blood. In the fading light I had pressed my eye directly up to the scope to see better and had paid the price for the added vision. My eyebrow had absorbed much of the recoil intended for my shoulder. But moments like this take place outside ordinary time and a minor wound was meaningless.

An hour later, the full moon rose in the black sky and cast strange shadows across the stage on which the cat and I had done our pas de deux. The sounds of the African night were at a fever pitch. The remains of the zebra hung in the pale glow of the fat moon. Nearby my trophy lay, awaiting our anxious inspection and measurement. We had hunted long, hard and persistently. I, more than anyone, had been rewarded. Now, would my old boy measure up to the others that had gone before him into the record books with respect to skull measurement and length?

“Well,” Con said. “Looks like the other bugger was scared off. Sometimes they stay around and keep at the bait, but not this chap.”

Rifles in hand, we crawled out the entrance of the blind and reached the Rover without incident. I stood up on the tailgate and held on as Con drove slowly along the dusty elephant trail to the scene of the recent action. As I waited in anticipation for my trophy to be unveiled, the headlights cast weird shadows across the brush.

Then, stretched full length across the trail in a kitten-like pose, I saw my magnificent, long-sought prize. He appeared so life-like I hesitated before dropping from the Rover.

On the ground together, Con and I were both grinning from ear to ear, shaking hands, simultaneous congratulations and thanking each other. We had two half-liter bottles of local Castel beer in our ice chest that we quickly uncapped to toast our success and the lion’s good fortune of becoming my rug instead of a meal for the vultures.

The trophy I’d coveted since childhood was mine. I was high with elation and exquisitely aware of everything around me. Every sound, every smell, every sight. Con and I leaned our rifles against the front bumper of the truck and sat on the tailgate drinking our beers. Together we gazed at the full mother-of-pearl moon hanging just out of reach above a baobab tree. All was right with the world.

“Well, Honorable White Hunter,” I said, “How are we going to get this beast into the truck?”

“Prayer helps,” Con joked.

We set about the task of leveraging 500 pounds of dead weight into the back of the vehicle. With rope, a small and inadequate “take along” hand wrench and an ample amount of sweat, we were able to get the animal halfway onto the tailgate. Adrenalin still pumping from our recent success made the work easier. After about a half hour of work, spiced with considerable conversation and stout beer, the job was nearly complete.

The tranquility of the shadowed glade where we were parked was suddenly shattered. A terrifying, blood-curdling roar came from mere feet away and froze us both in position for a millisecond! Fortunately, no savage attack followed. Con and I collided as we simultaneously dashed for our rifles at the front of the Rover. While wallowing in our euphoria, we had become careless and let our guard down.

I followed Con into the open bed of the truck and stood with my rifle at the ready. With a small flashlight, my white hunter found the large maneless male who had been the companion of my lion. His eyes glowed devil-like from only ten paces away. He was in a crouch and ready to spring, his tail nervously flicking from side to side.

“Would he come after us here? I asked in a whisper.

“Yes, Hell yes!” Con answered. His voice was intense.

We adversaries, two men and one large cat, glared at each other across the short distance, flashing back a million years in time. The near-freezing night air chilled me suddenly as I mentally reviewed the drill for a charging lion. Shoot him in the mouth, and so forth. I quickly contemplated the difficulty of hitting a lion in the mouth that was charging at me in the dark. My confidence could have definitely been higher.

Low guttural sounds came from our unhappy adversary on the ground. We hunters had our rifles to our shoulders and our cheeks to the stocks, sighting down the length of the barrels. What seemed like an eternity passed. Overhead the Southern Cross was suspended in the cold, cloudless sky. The lion spat out more ominous growls as we fidgeted with our rifles. No commitment was made by either party. The baleful eyes continued to glow in the beam of Con’s flashlight. Then after what seemed a small eternity, Con spoke.

“I’ll try and scare him away.”

Mmm, I thought. Just what does it take to “scare” a lion?

My Afrikaner friend proceeded to verbally abuse the lion, making offensive remarks about his parents, his friends, his morals and his upbringing. This had to be a pretty laid back lion, as the forceful verbal assault didn’t faze him one iota.

“One last effort,” said Mr. Van Wyk. “I’ll fire a round over his head.”

FLASH! BAM! My ears rang, spots danced before my eyes and the smell of cordite was in the air—and the lion was still there. He threw his head in the air and issued forth a genuine MGM roar. I had no doubts the situation had become deadly serious now.

“We shall retreat,” Con suggested. “We’ll crawl over the side of the truck very slowly and deliberately and back toward the safety of the blind. Keep your rifle up and ready at all times.”

Once over the side of the Rover we lost the advantage of being able to see the beast. With the vehicle between us and the enraged lion, we backed toward the blind, feeling for each step, our senses at the ready. Could we reach the blind, about 15 yards through the dark and the brush, or would we literally be cut off in a flank or frontal attack?

We finally reached the flimsy sanctuary, crawled back into position and carefully arranged the brambles in the entrance. My breath came in great blasts now. My heart rumbled in my chest. It was doubtful a few briar twigs would even slow the advance of a determined lion, but at least it gave us a sense of security, albeit false. I pulled my sleeping bag around me and remained on the alert, thinking for the first time about my unprotected trophy. Suppose a pack of roving hyenas decided to devour it.

We stirred with the morning, having spent the balance of the night without further incident. Outside the blind in the dust, tracks were everywhere. We surmised the maneless lion had followed us back to our small, circular enclosure of branches, reeds and cut thorn bushes and sniffed around the entire area.

Cautiously we returned to the Rover and found my lion still stretched out on the tailgate, stiff now, but lifelike, even in the repose of death. The black and ginger mane ringed his face and neck like a regal wreath. We quickly completed loading without the hoopla and fanfare of the previous evening.

Once packed and ready to start toward camp, Con discovered we had no clutch. Good fortune was with us again as the battery was strong enough to start the vehicle in gear. Away we went under a sky that was rapidly turning a bright shade of pink. Later in the day we found out that our nemesis, the maneless lion, had followed the Rover for over two miles as we slowly ground along the game trail.

The fence gate at the lodge closed at sundown and opened at sunrise. We assumed it would still be closed when we reached camp, so we had to come up with a plan. Without a clutch, we’d be unable to stop the vehicle on the steep road into the camp, so after a few words with Con, I jumped from the Rover while it was still moving and ran up the short hill to the closed gate. Con drove slowly around in circles until I had it open, then as he chugged by I swung back aboard. At just that instant, the sun crested the rim of the horizon and its golden rays sliced through a pale magenta morning like bolts of lightning. I’ll never forget this moment,” I thought to myself. To this day, I haven’t.

Good news spreads fast. Within minutes of our return, it seemed every single member of camp gathered around to look at my lion. Even the smallest children were there, all eyes and white toothy grins. In Africa, the taking of a trophy lion is a spectacular occasion and cause for celebration. There wasn’t a sad face in the crowd.

Lions have always been predators. Man has been a predator from at least before history. Perhaps by the Stone Age, man became at best co-dominant with the massive cats. A lion trophy obtained by hunting prowess has long communicated qualities like bravery, strength and skill.

Cro-Magnon artists featured the lion as a symbol of power and as a prestigious quarry. These felines are mentioned in the Bible more than ten dozen times. Eight European monarchies utilize the lion as symbol of dignity and power. No single animal has received more attention in history.

The lifeless lion at my feet signified that I had made direct contact with my forebears, my evolutionary roots.

The first black man who came up and clasped my hand was Charlies, the smile on his face as wide as all Africa. Genuinely elated, I detected the slightest mist in his dark eyes. I’ll never forget the sincerity of his praise and congratulations at that moment. Seldom are true sentiments such a plain matter of fact. For the moment, I felt like a God on Olympus. Invulnerable.

The celebration breakfast consisted of soft scrambled eggs, lightly sauteed impala liver, fresh sliced tomatoes from the garden, freshly baked bread and a bottle of Dom Perignon champagne. After we had finished, it was time for the obligatory photo session, measuring, skinning and storytelling. In other words, a time to puff out my chest and exaggerate, to bask in the attention and reel in the glory of it all.

My father skinned the lion with a special McBurnette lockback knife that an old and dear fellow sportsman had given me. We awarded a small trim of whiskers, the testicles and the body fat to Charlies, who in turn gained much status and esteem with the witch doctors. Four parts of the male lion are magic, and Charlies had three. The fourth, the floating collar bones, about the size of a turkey’s wishbone, would make a “black magic” necklace for my long-suffering wife, my “mama,” as all white women seem to be called by dark Africans.

My lion measured 118 inches long when cold and stiff, which meant he probably would have topped 10 feet when warm. His weight was estimated at around 520 pounds. His skull was officially measured at 9-3/4 x 14-3/4 inches, making him the 46th largest lion in the Safari Club International record book.

His stomach contents seemed to be mainly zebra meat, which was logical and included a patch of zebra skin about the size of two sheets of paper. Charlies had one of his wives tan this for me, and a strip of it now adorns my hat as an extraordinarily special band. The carcass and stomach contents were delivered to Dr. Vernon Booth, Chief Ecologist, National Parks and Wildlife for examination and review.

The sun was well up in the power blue sky as I left the skinning shed still surrounded by a large crowd of the curious. My life had irrevocably changed. I had met the King of Beasts in a fair encounter, and I had persevered. I was a member of one of mankind’s oldest and proudest clubs. Like those who preceded me, I knew that the joy of belonging can only be experienced, never really described or explained. At long last, after half a century, I had come of age.

FINIS

EPILOGUE

A few months after our victorious safari, my hunter Con was with another client. Early one morning, they had the good fortune to bag a jumbo elephant, so they returned to camp to round up the skinners. Arriving back at the carcass, they spooked five large lions that had settled in to enjoy the 5-ton feast. Since the hunter had no lion trophy, a blind was hastily improvised to await the return of the hungry cats. The wait was short, and soon Con was signaling the best prize. The client’s shot struck the lion far back, and with a roar it disappeared into the bush.

Alone in the growing darkness, Con followed the trail of blood, his rifle at the ready. With an awesome roar, the lion launched from 15 feet. Practicing what he preached, Con fired his .375 H&H magnum into the lion’s open mouth at the last possible instant. With a tremendous noise, cat and man went down.

The lion soon had the professional hunter’s entire head and right arm in its mouth. Accompanied by guttural growls, the lion began to maul him, intent on a kill.

The client ran toward the horrific struggle, but initially could see nothing, only hearing the terrifying sounds. He saw movement in the brush. Then suddenly, quiet. There lay a still dead lion atop a blood covered man.

Fortunately Con’s shot had broken the lion’s lower jaw, prohibiting a full bite. The bullet shards then sliced through into the lungs, eventually dispatching the beast. Con luckily escaped with a severely mangled, but repairable arm and a lacerated scalp. After 150 stitches and a few weeks of hospital and recovery, he is back on safari.